A retrospective exhibition of drawings and paintings by Anthony Terenzio opened yesterday, February 8th, 2025, at the Nancy Devine Gallery in Warren, Rhode Island.

Anthony (Tony) Terenzio was a prolific twentieth-century Modernist painter and revered university teacher from Connecticut, much of whose life’s work was tragically lost in a house fire several years ago. Nancy Devine was able to gain access to a handful of pieces salvaged from the flames by Tony’s family, and I contributed a small archive of drawings and one painting from my press and former gallery in New Mexico, where I had briefly represented Terenzio in the mid 2000s and also published a limited-edition book about his life and work.

One of the first essays I ever wrote about another artist, which was included in my Terenzio book, describes a visit I paid to Tony’s studio in 2002 with my own longtime painting mentor and friend Peter Devine (Nancy’s late husband) not long after Tony died. Tony had been an instructor at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, where Peter studied with him in the 1960s, and from which beginning their own long and close friendship had grown and thrived.

In the late 1970s, I briefly met Tony when he visited the Woodstock school in Vermont where Peter was then teaching me. I didn’t ever get to know him beyond that glancing hello, though I heard about him often enough in later years. It was only after Tony had passed, when Peter recommended me to his daughter Lisa as a photographic archivist for his estate, that I finally met him properly, albeit in the form of the large collection of drawings and paintings he’d left behind.

There are so many artists working now, so many thousands of images posted on social media sites like instagram and facebook, on innumerable galleries websites, and in the reams of self-published catalogues, blurb books, postcards and other ephemeral records that rain down like ticker tape on a motorcade of returning astronauts, that it is difficult in such an onslaught to find one’s way to any reliable compass of critical discernment. The overarching ethos of the age are the conjoined presumptions that, A. If I made it, it must be art, and B. If I made the art, it must be good.

Neither is necessarily true.

Still, too many aspects of art’s meaning and purpose today are too variously defined, too subjectively measured to allow for any over-arching standards against which it might be dependably judged. It is possible though to say that Tony Terenzio was both a very good, as well as an historically significant painter of his time, and to at least identify those factors which made him so.

To begin with, Tony drew beautifully, and did so with a classical grace that is subtly woven throughout the otherwise edgy, abstracted formalism of his daily sketchbooks. Peter told me that day in the Connecticut studio that, much as a chain-smoker will light the next cigarette from the embers of the last, Tony almost always had a pencil or a stick of charcoal or conté crayon in his hand. This was borne out by the enormous volume of drawings we encountered there. As many as there were, there was also a consistency to them. Tony found a clear graphic voice early-on, then stuck with it right through the several phases of his painting that traverse the postwar decades. From the 1950s to his death in 2000, drawing became a daily, if not even an hourly exercise for toning the muscles of his visual acuity.

There is a seemingly frenetic, stream-of-consciousness quality to these drawings, but on closer inspection they are always thoughtfully, deliberately assembled. One has the sense that every line in what might otherwise seem a chaotic weaving of warps and wefts has its exact place in relation to all the others, without which placement the whole could not stand. This was the sub-frame on which all Tony’s paintings were subsequently built, and as much as each cycle of his mature work stands distinctly apart from the others, the architecture of his drawing is the binding agent of his whole vision.

I said above that Terenzio’s work is historically significant. The same is said of practically every pulse in the heartbeat of contemporary art which finds an approving critical audience or any sort of artworld “buzz”. But it is only sometimes true that the works so lauded have legs strong enough to withstand the next shifting cycles of fashion or taste. Artistic movements, theories and identities come and go with the seasons. Tony did receive some modest acclaim from time to time. Despite having spent much of his career at a regional college, remote from the bustle of the big city’s marketplace, he was not unknown in the world of art. He showed in respected galleries in New York early on, where he received favorable notices, and was later included in important regional museum exhibitions. In the early 1980s, the painter Robert Motherwell met Tony and became so impressed with his work that he included him in a survey exhibition of renowned Connecticut painters at Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum in 1983. Motherwell also recommended him in 1986 for the prestigious Frances Greenburger Award, which was bestowed in a special event at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. In 1992, a solo how at a Hartford Gallery was also reviewed with praise in the New York Times.

While that handful of distinctions may validate my claim of Terenzio’s art historical merit, its real substance resides of course in the work itself; in its originality and refinement, and in the unique way he blended his European roots with the American voice that evolved from them (born in Italy in 1923, he had emigrated with his parents as a boy from the small hilltop town of Settefrati).

Though belonging to the same generational cohort as other figuratively-oriented American Modernists such David Park, Richard Diebenkorn and Fairfield Porter, Tony descends from an Italian tradition that incorporated Modernist ideas, but also comfortably referenced influences stretching as far back as the Renaissance and even to Classical Rome and Greece. His titles are full of literary allusions and his imagery was often built on ancient formal ideals. There are also always references in Terenzio’s work to other painters who came before, and even occasional nods to some contemporaries like Diebenkorn or Guston. But he is original not only in spite of such acknowledgements, but also because of them. In an age when it was considered sacrilegious to betray the slightest interest in what had come before, and to strive for the appearance of novelty and innovation at almost any cost, Tony seems to have been quite comfortable with the past. He likely felt that, as a painter, he was nothing if he was not part of art history, rather than apart from it. So when we see a vestige of Giacometti, or some other earlier or even contemporary painter in his compositions, it never feels like an imitative pastiche. He pays homage to the artists he admires, rather than copying them, much as a Jazz player will reinterpret a “standard” and transform it into something new and original, but also historically nuanced.

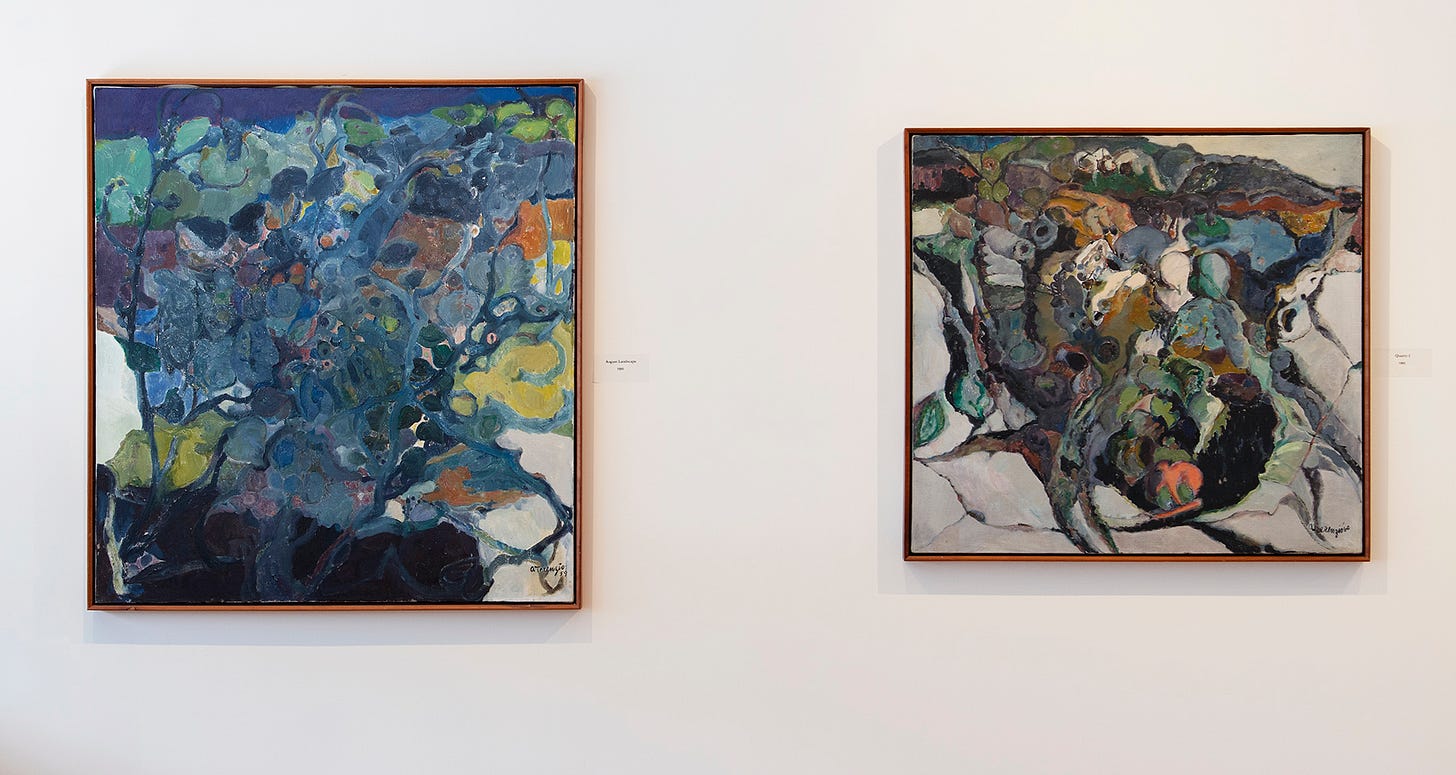

There are four distinct cycles represented in this show at Nancy Devine’s. The first, from the late 1950s and ‘60s, is a landscape form rendered in all-over compositions of serpentine skeins of vegetation. There is no dominating horizon in these early pictures, no immediately apparent depth of field, save that implied in the undergrowth weaving in and out of the green and blue foliage that overspreads the slightly off-square ground of these medium-sized canvasses.

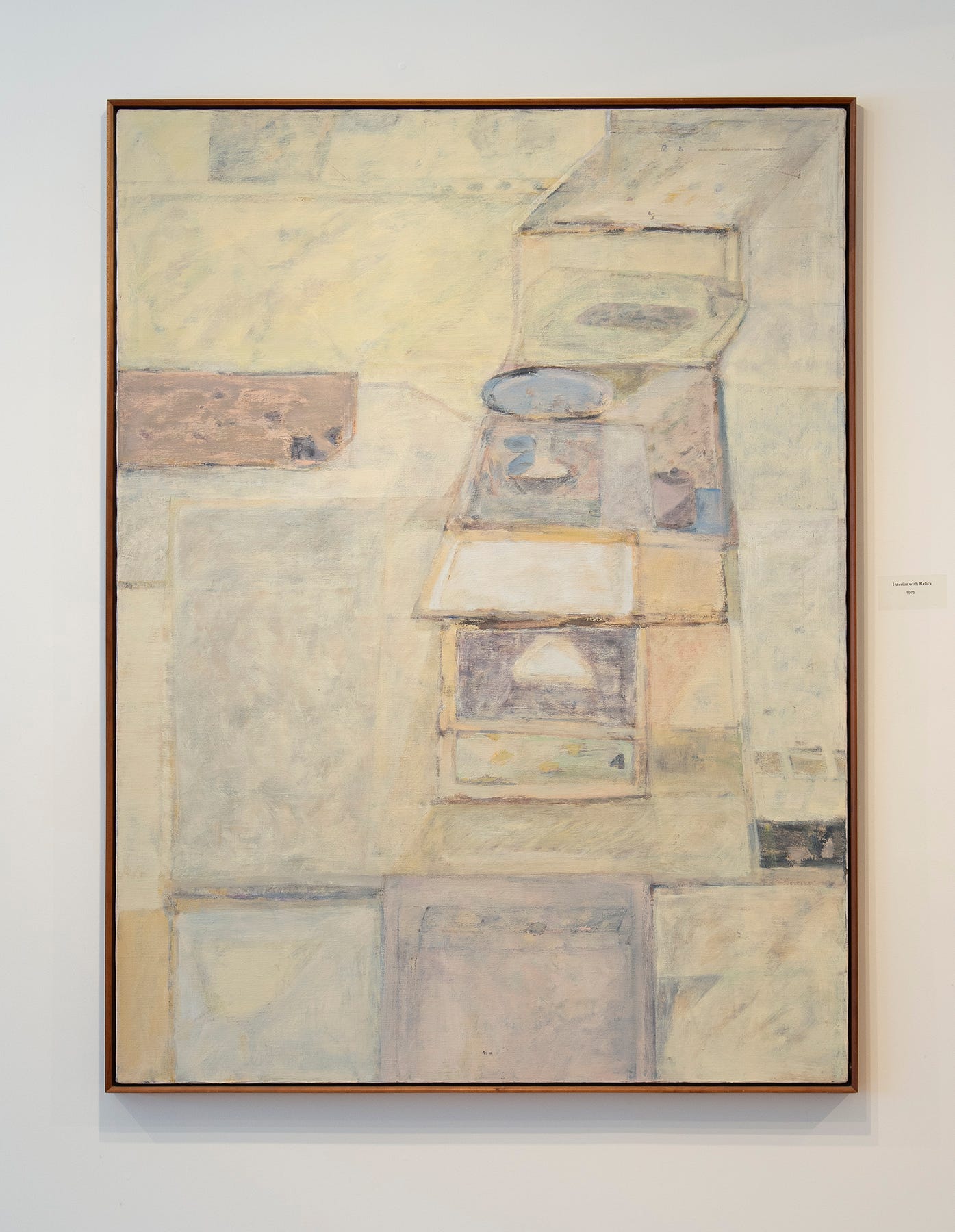

The next phase, traversing the 1970s (and one from which we could only access a single loan from a collector, the others having been mostly lost in the fire) were a series of large, vertical, semi-abstracted studio interiors of table tops, windows and occasional still-life objects. These works can remind one of Bonnard’s interior spaces and shapes, but they are so subtly-hued as to be almost monochromatic, so that his spaces are not defined by the kinds of electrified chromatic contrasts Bonnard used, but in a tonal scale traversing the very slightest variations within an otherwise predominant color. That, finally, was the language on which Tony settled after his first experiments with those brighter botanical compositions. For the rest of his life, the paint became a tool for drawing. As such, it is less a language of hue than of texture and line, the pigment adding a visceral dimensionality to the brush-drawn calligraphy of his marks; a push and pull between surface and ground that becomes his primary language of description.

The majority of the surviving paintings, and those which strike the most dramatic and fully fleshed-out note in this exhibition, are from Terenzio’s late Odyssey series. With titles like Scylla, Icon For No Worship, and Nausica, these raw, gestural studies in blacks, whites, rusty browns and pale yellows suggest mythical beasts, heroes and heroines, ruined monuments and tangled mats of possibly organic, possibly mechanical detritus. It has always felt to me a dark and troubled vision, and they can sometimes be challenging to look at for long; they are so fierce in their refusal to bend to the picturesque or other comfortingly familiar aesthetic devices.

I do know from Peter that Tony grew increasingly frustrated by the artistic trends and ideas of his time, and while his works feel both intellectually complex and literate, they are not instructive or illustrative of any particularly identifiable concept. They invite the viewer to come into them and risk a Minotaur’s labyrinth of veiled portents and literary allusions that are more suggested than explained. Whatever they may mean, they are powerful and uncompromising in their demand to be met exactly where they stand.

The last two paintings in the show were made in the late 1990s when Terenzio had become ill with the cancer that would eventually take his life, too young, at seventy-seven. The first of these, a composition titled Island, in bright blues and saturated reds against a light ground, feels playful and hopeful after the dour expressionism of the Odyssey cycle, even suggesting a possible emergence into some lighter psychological place.

The final, untitled picture (which we believe to be the last canvas the artist ever completed) again becomes darker, in arid reds and blacks and with some fountain-like blue passages. But it also feels more winsome and perhaps a bit resigned than the blackened Odyssey pictures. It is the only one of Tony’s paintings that I have ever seen which shows a more conventional landscape with fore and middle ground, a horizon and a band of sky at the top. It looks like a cluster of houses rising into the distance, perhaps to a small, hilltop Italian village. Tony seems to have come home at last to his own Ithaca. A relieved return perhaps, but also one fraught with the discovery of an altered landscape, and his own now unfamiliar identity and psyche, irretrievably transformed by the long campaign away.

Nancy Devine Gallery is located at 57 Water Street in Warren, Rhode Island. The Terenzio show runs until March 23rd, 2025.

Gallery hours are Friday to Sunday, 1 to 4 pm, or by appointment by phoning (917) 697-6383

Grazie Mille for your engaging words and style that heightened our interest in seeing the show. Thanks to your insights, complemented by Nancy Devine’s as well, it was a deep joy to spend time today in her gallery surrounded by Tony Terenzio’s vision and energy divine — so too Peter’s (divine and Devine), whose spirit remains palpable and ever-inspiring…..

Great story, I was wondering what you were up to