One of the things that can happen when embarking on a life in the arts is that, right from the starting gate, it encourages a refusal to follow the course mapped out by the race officials. This can be tricky, because nobody needs art in quite the same way that we need food, housing or healthcare. A good farmer, carpenter or doctor is probably always going to be able to make a living, but a truly great artist could just as easily be overlooked, spending a lifetime piling up work nobody wants and which some poor family member or friend has to dispose of after they have died. Because of this, there is always some tension between the impulse to follow one’s own vision and to make things that will put food on the table. The “race officials” alluded to above are those individuals and institutions that artists in any age come to rely on for that support. In earlier times it was the King, the Church or The Academy who dictated what sort of art might find a market. In my lifetime, it has been the big, chaotic, and now highly commercialized realm we refer to as “The Art World” — a hydra with many heads emanating from and to a range of institutional entities and influential taste-makers, including the “top” art schools, museums, galleries, fairs and auction houses and a whole cabal of critical interlocutors, curators, historians and consultants who parse, evaluate and hand down evaluative judgements on artistic things.

Sticking to my own medium, which is oil painting, most of my favorite artists throughout history became successful (which is to say that they made names for themselves that history saw fit to remember) by only partially following the conventions that prevailed in their time — including, by the way, the tenets of whichever revolutionary movement may have been cycling through the art historical line at that moment; because, as Marie Antoinette or anybody who dared oppose the Russian Bolsheviks could have told you, there is no more tyrannical authority than a revolutionary. But, almost all the old painters whom I like best (Rembrandt, Gentileschi, Goya, Turner, Manet, DeKooning and Neel to name a few) also found ways, sometimes overt, and at others quite subtle, to throw the rules out and go their own way. Even when they were closely following the rules, these people only became successful because something about what they were doing was sufficiently unique and individual, or enough of a divergence from whatever conventions they were otherwise following, to enable them to stand out in a crowd of practitioners who hewed more doggedly to the map. It would seem then that the paradoxical lesson for the artist is that history remembers the rebels who most successfully follow, yet also simultaneously break the rules.

None of this unfolds in some rarified vacuum apart the rest of the ordinary workaday world. As I have frequently observed in these writings, art is nothing more or less than a mirror held up the whole of human experience and affairs. As it happens, we live in a world founded on the belief that there is always some authoritative entity, be it a god, a leader or an institution, which possesses superior knowledge to our own and by which knowledge it is entitled to dictate right-thinking and right actions to the individual. This notion is so deeply baked into our culture, and many other cultures as well, that to even imagine a different way of doing things is almost unthinkable. Because we believe so completely in that authoritative voice, wherever we happen to situate it, we are hopelessly vulnerable to the whole panoply of tyrannies that authority, by its very nature, poses.

The world we are living in today is fracturing and failing in so many different directions all at once that it can feel that we are careening towards an inevitable and overwhelmingly insoluble disaster. But perhaps we might consider for a moment that one of the ideas driving us towards that precipice is the tyranny of the ideal of innovative progress. I encountered this as a young painter when I fell in love with the magical way that pictures made in my medium could describe the world, but was then told by the reigning race officials that it was no longer respectable, legitimate or meaningful to make pictures at all; in other words, that we had moved beyond such things and in so doing, had rendered them wholly meaningless and anachronistic. This, we young painters were informed, was progress, and because progress was both inevitable and righteous, we had neither the power nor the right to reject it. If we did so, we must accept that we would be seen as unintelligent, backward and insignificant. My immediate and intuitive response to this information was “Oh yeah? Well, I’m gonna make whatever the hell I want, because what I like to make is still wonderful and the things you want me to make are no more wonderful, however interesting or ‘innovative’ they may be.”

It wasn’t that I objected to new things. I started painting in the early 1970s, when Abstraction and Pop Art were the reigning and correct newer forms. I actually began experimenting with abstraction as early as my freshman year in college in 1979 and had a lot of fun doing it. Now in my mid-sixties, I’ve been painting abstractions right alongside my representational pictures for over twenty-five years. So it was never the case that I disliked that sort of painting, or ever thought it a lesser or a more stupid kind of art; I only felt that those commanding me to work that way, or in any other fashionable idiom, were — at least in that one respect — lesser and stupid people. Because I refused to follow their instructions, I’ve spent my life doing something entirely my own and which I have thoroughly enjoyed. Not only that, I got to be quite good at making the kinds of things I do make and have even made a decent living at it. It turns out that the world is full of people who are no happier about being told what sort of art they should like than I was happy in being told which kind to make. Many of these people cheerfully, even enthusiastically, buy my paintings of both kinds.

All well and good for art, but are there other tyrannies we might profitably resist in order to lead a personally satisfying life? I can think of a central one that has been ruling the western world (and all our cultural colonies across the globe) for the past several centuries, and of which all that I describe above is a reflection: these are the conjoined tyrannies of innovation and of its authoritatively proclaimed inevitability.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for innovation. I love it and always have — just as I have always loved abstract painting. I have followed and relished and in some way utilized many of the most promising inventions that science, industry and technology have brought us in my lifetime. But I wholly reject the notion that we must accept as inevitable, or even righteous, any of those more objectionable by-products our inventions might create simply because they are innovative. I would even go so far as to say that many things which are served up to us as groundbreaking innovations are in truth only regressions posing as novelties.

I was once invited by a technologically savvy and innovation-loving uncle to attend a lunch in the San Francisco Bay Area with a group of influential technologists from Silicon Valley. It was an informal gathering around a big round table at a popular Berkeley taqueria. I was in my mid-thirties at the time, and most of these folks were the same age or only slightly older than I, so it felt like an easygoing and open conclave.

I sat quietly for a time listening to these guys gush about the coming revolution of the internet and how it was going to usher in a golden age (there were all men of course, the newly-fledged goslings of the tech-bro generation). This was in the early 1990s, as the internet was just beginning to pick up some steam, but when most of us still had to rely on dial-up connections to get to it. As these jokers held forth in torrents of rapt self-congratulation, a couple of things quickly became clear. First, they all thought they were geniuses, and second, they were already simultaneously brewing and guzzling down the toxic Koolaid of what they clearly regarded as a manifestly-destined brave new world order.

At some point there was a lull in the conversation and into the silence I offered some version (can’t remember the exact words) of the following observation: “The internet isn’t new; it’s only a bigger, more insidious version of the television — a way to make even more money selling us shit we never knew we wanted and probably don’t need. You guys aren’t changing the world for the better, you’re just inventing faster ways to fuck it up.”

I may as well have gotten up on the table, dropped my shorts and peed into the guacamole. The response on all their faces was, by rapid turns, a silent shock, followed by offended consternation and finally, total dismissal. Nobody answered my point, nor did anyone say a word to me after that. It was also clear that I had embarrassed my poor uncle, who was probably chuffed to be included in that company and regretted inviting me to tag along.

So was I right? Has the internet turned out to be a bad thing? Yes and no. It is not in itself a bad tool. It is in fact a wonderful and very useful tool. But we have used it to intentionally do some very bad things, and a great many other equally bad, if unintended, consequences have also arisen from that use. The failure to anticipate and protect against those more negative downstream consequences of its invention is not down to any inherently malicious quality in the tool, but in its users. One can say the same of every one of our technological innovations as far back as the wheel and the long-bow. The point is that while we have been discovering and implementing technological advances at a breathtaking and exponentially accelerating pace ever since that first person thought to put an axle in the center of a rounded stone, our own intelligence about the best use of such things has not advanced by a single faltering step. The gleeful self-satisfaction and hubris of those young technologists at the table in Berkeley was plausibly identical to that of the wheel’s inventor and of every inventor since, from the creator of the first ruddered sailing vessel to the men and women who built the atomic bomb and those who are now feverishly developing Artificial Intelligence.

This blinkered infatuation with “progress” may well be the defining Achille’s heel of the whole human experiment. Even as we embrace some innovations, there are always other impacts of their arrival that we will find reason to regret or even abhor. The problem is that we have all been too well trained to think ourselves dull, stupid, conservative or backward should we choose to express — much less act upon — that abhorrence by choosing in some way to either regulate the use of the new thing, or else turn away from it altogether.

I don’t recommend that anybody forsake their modern lifestyle, as some social or religious sects, such as the Amish do, for wood-fires, candlelight, hand-tools and a horse and buggy. As admirable a position as that may be in some respects, it is also avoiding, rather than grappling with, the challenging problem of how best to live in a technologically innovative culture. But neither do I believe that we have no choice but to accept as either inevitable or correct all the unpleasant realities that innovation breeds. I can shop at a supermarket, but I don’t need to buy the foods there that are encased in disposable plastic clamshell containers. And if I find that the market I frequent has resorted to packaging all its wares in that way, I can look for other places to buy things where that is not the custom. Equally, as a skilled and even enthusiastic user of certain computer programs and systems, I do not in any way need to accept the inevitability of so-called upgrades to their programs when said improvements only undermine, interfere with, or otherwise obliterate the smoothly efficient workflow of some earlier, better version.

What I discovered as a thirteen-year old on first picking up a paintbrush to try and make a picture, was that making pictures in that way was challenging, pleasurable, fulfilling (if I learned to do it well) and also a way of eliciting pleasure and wonder in others. When I look at the very earliest works of art that humans have made, I tend to find them no less beautiful, sophisticated or movingly human than many things being made today. In fact, by those measurements they are sometimes superior. Similarly, we can experience the very newest and most innovative art forms as equally exceptional to all that came before so long as they too are relatably human and moving. But it does not necessarily follow that any of us also needs to make things in that way. When, at age sixteen, I attended a major museum retrospective of the Modernist painter Richard Diebenkorn’s work, I did not experience his more abstractly modern pieces as a negation of the very different, and more traditional, types of pictures I liked to make at the time. Neither did I receive them as a commandment to do things in his way. I simply saw them as a brilliantly engaging variation on the same music I already loved to listen to and make, and which music was not rendered any less moving or meaningful by the arrival of his variation.

Together with a near fanatic devotion to innovation, ours is a culture built on an equally idolatrous worship of the idea of “Genius”, believing in the process that its piercingly efficient, quantitative mode of reasoning is the apotheosis of human intelligence. We even invented a special test to measure this quality, giving it the ridiculous name of the “IQ (intelligence quotient) test”. But as impressive as it may be to behold, the calculative virtuosity we have lately come to think of as genius has virtually nothing to do with actual human intelligence, which is a far subtler, more nuanced amalgam of reason and intuition distilled through the experimental matrix of lived experience. There is an older, more telling descriptor than genius for that sort of intelligence. We call it Wisdom. Maybe it’s time for a test which measures that quality.

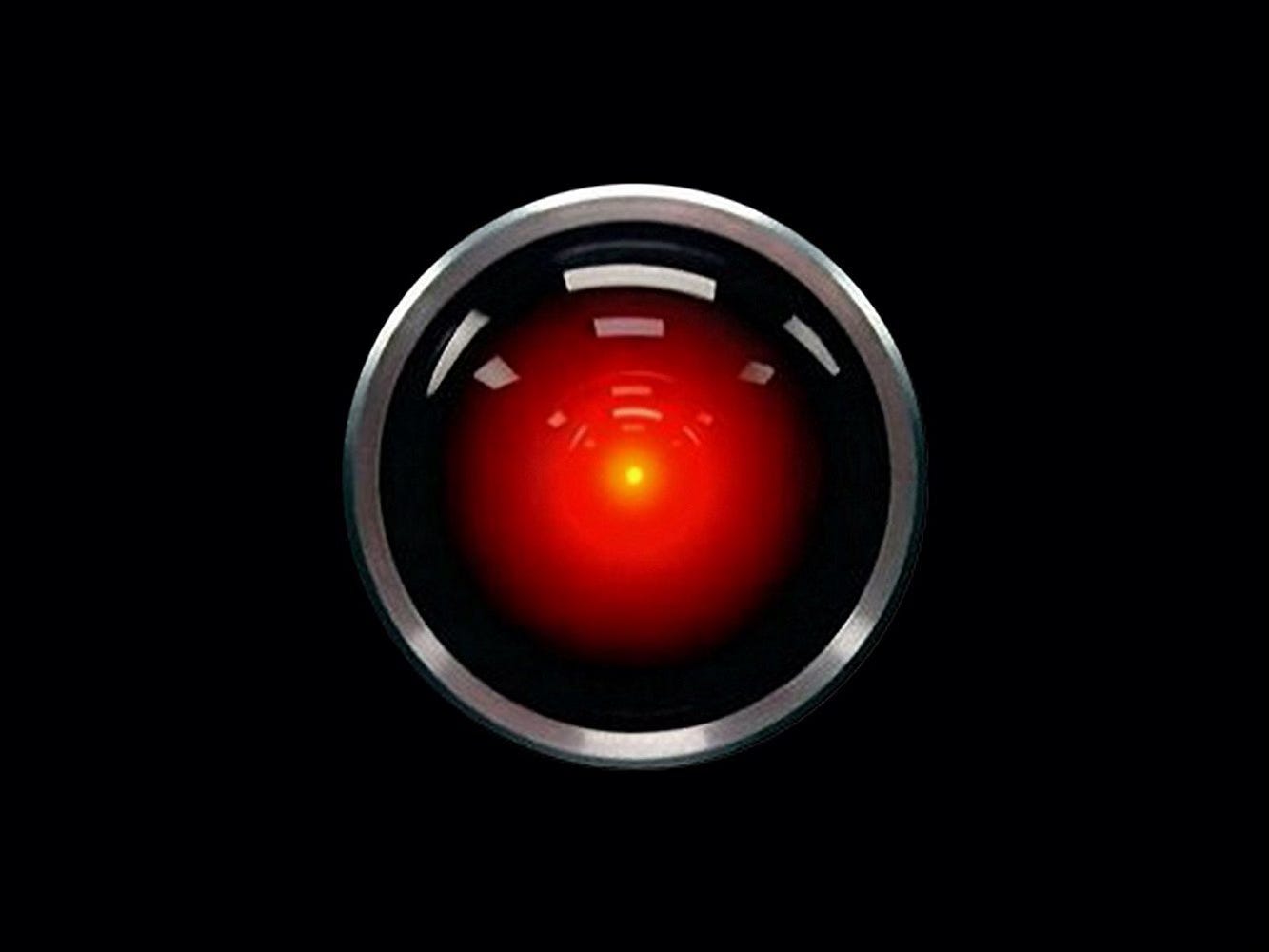

There are some who believe that AI is the latest and most significant evolutionary step our species has yet made, and that as such it will inevitably leave us behind in the dust of our hopelessly limited and primitive natures. I submit here that this will only happen when the tool acquires the wisdom to understand, as we never collectively have, that innovations are neither intrinsically good, nor that the bad events and outcomes they can precipitate should ever be accepted as inevitable. Whenever AI figures that out, it may indeed surpass us, but in the meantime it will only enable us to get everything wrong, faster. I suppose that the day might come when it does learn how to be wise, but I will stubbornly stick to the, possibly delusional, hope that we humans might finally figure that one out for ourselves.

I too have often expressed my belief that intelligence and wisdom are two entirely different faculties, and I still hold to it; I see the latter as involving the heart as well. Recent research on the physical human heart has revealed some very interesting data; speaking of AI, I just asked Google AI "Does the heart have the capacity to function somewhat like the brain?" and this was the response:

"Yes, the heart possesses its own sophisticated nervous system, often referred to as the "little brain" or "intrinsic cardiac nervous system," giving it a capacity to function somewhat like the brain. This "little brain" contains neurons and circuitry that allow the heart to learn, remember, and even feel and sense independently of the brain."

Perhaps even more fascinating is this (also from Google AI):

"The electromagnetic field generated by the heart is significantly stronger than that of the brain. Research suggests that the heart's electrical field is about 60 times greater in amplitude than the brain's. Furthermore, the heart's electromagnetic field is estimated to be 5,000 times stronger than the brain's."

A well-written article Chris, your sentiments shared and appreciated (from a lover of Graham Nash, Bjork and many things in between).

"...First, they all thought they were geniuses, and second, they were already simultaneously brewing and guzzling down the toxic Koolaid of what they clearly regarded as a manifestly-destined brave new world order...."

And they're all still doing that to this day, and that will not change into the future either. Arrogance, hubris, and self deception seems to be de rigueur in many industries and none more so than tech.

Yes, dangerous to confuse genius with wisdom

Great post Christopher.