1. Apprenticeship

Alongside a long career as a working oil painter, as well as various other trades I’ve picked up and plied along the way, I have also been a carpenter of one sort or another for over fifty years. I began working at these jobs at age 13, when I spent a few summer weeks as the “go-fer” on a waterfront construction site in my hometown of Newport, Rhode Island under an irascible and notoriously alcoholic Portuguese contractor. My whole responsibility in that first engagement with the trades was to

“. . . pick up the shit, and put it in the shit pile!”

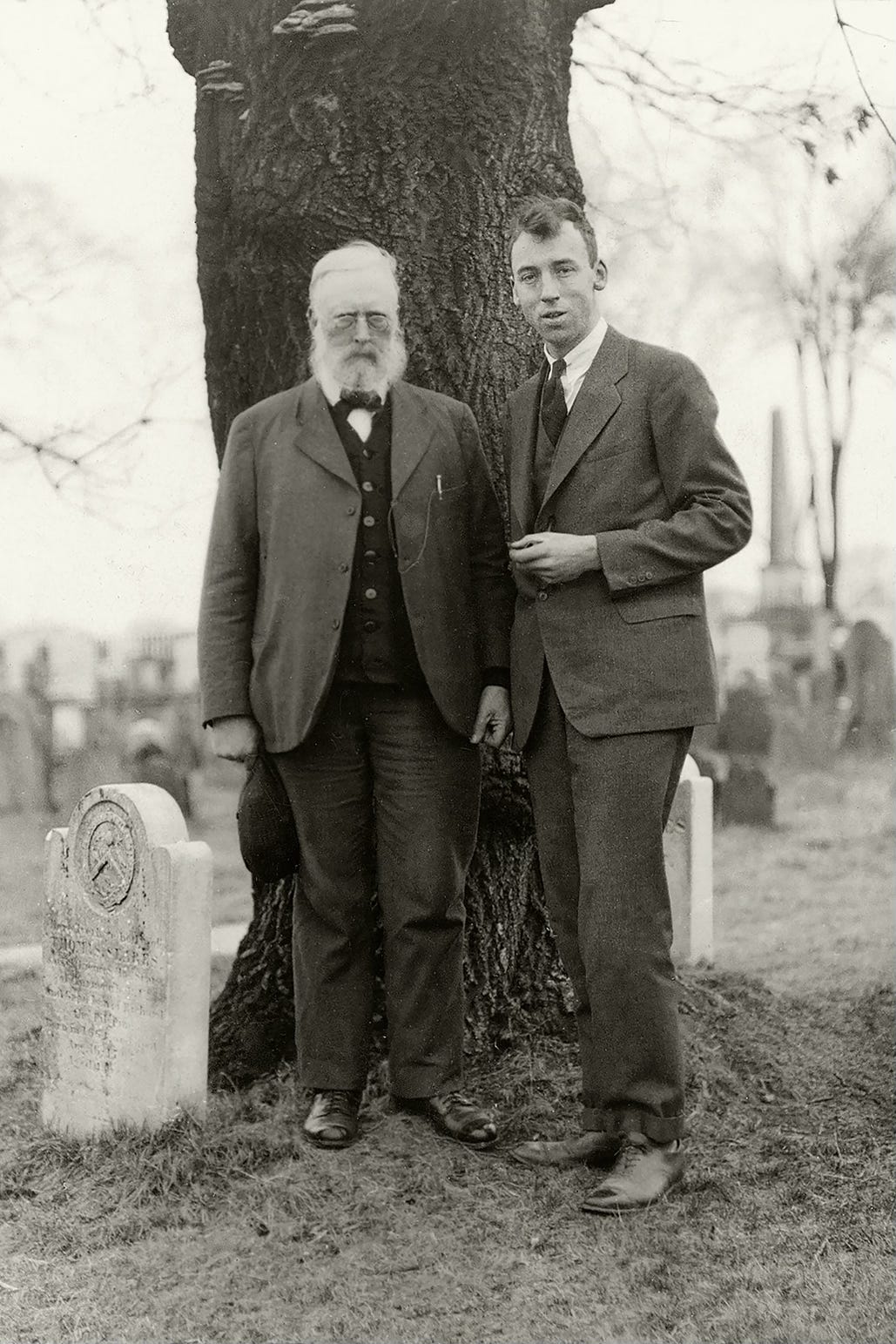

There followed multiple summers of similar, but increasingly demanding sojourns, under a cast of equally colorful employers. I worked one year for an older artist friend painting sets for a TV miniseries (The Scarlet Letter) which was filming at an old granite fort on the harbor. In another summer, a soft-spoken and gentlemanly art historian hired me to assist in the restoration of 18th century slate headstones in the big colonial cemetery that rolled down the hill behind our family house. Other stints with a couple of different contractors followed in subsequent years, as well as working while in college at the nearby Rhode Island School of Design on an extensive renovation to the upstairs and back workroom of my father’s centuries-old stone carving shop.

To my father’s dismay (and not a little fury) I washed out of art school at twenty-two (RISD was a bad fit for me, and I a bad fit for the school) and moved down to Brooklyn, New York where I landed a job with three young, self-employed cabinetmakers who had all cut their teeth in bigger production shops in Manhattan. The first was a serene, Zen-like Japanese artisan in his early thirties — a neighbor of my mother’s in Boerum Hill — who offered to hire me shortly after I’d arrived in the city and begun camping in her basement. Next in line was a haughty Swiss-German schreinermeister, the graduate of an exacting apprenticeship in a famous trade school in Basel, who never failed to remind the rest of us of the vast superiority of his European artisanal pedigree. I ended up, though, working mainly for the third guy, a pragmatic, hot-tempered Italian American from the midwestern steel belt of Ohio and Pennsylvania (I’ve often said he could have medaled in the hammer-throw). His fractious style and personality were as distinct from the comparative craftsmanly serenity of the other two as one might imagine. He was a natural-born hustler, with a perhaps shrewder, but certainly more pragmatic business-sense, and a readiness when needed to sacrifice material perfection to the swift and able-enough completion of the job at hand. These traits brought him the occasional derision of his shop-mates, but they served him well enough going down the road, as he is still at it today, in his own shop, where his fellow makers have each suffered some subsequently challenging professional and economic setbacks. His rather aggressive persistence appears to have paid off in other ways too, for he has blossomed over the years into a fine furniture and panel builder and an accomplished architectural restorer, not to mention an astute essayist on craft and the artisan’s life.

At the time when I joined though, these three makers — two of them still in their twenties themselves (the Swiss man may even have been more or less my own age) — shared the rent and equipment in a cooperative shop in an old brick factory building on Front Street, directly beside and beneath the eastern landing of the Brooklyn Bridge. Unlike my previous summer jobs, this one was a full-time position which soon grew into a genuine apprenticeship. I worked in rotation for all three men as they gradually went their separate ways over the next six years — some starting their own shops, moving away from the city, or working for other companies — until I finally went independent myself in my late twenties, then moved west. Together, they trained me to be both a craftsman and also a self-employed, self-defined economic entity, the antithesis of the white-collared company men and women then proliferating across Ronald Reagan’s, and later Bill Clinton’s, rapidly corporatizing America.

2. The Living History in Things

I had a beloved uncle (I’ve written about him here) — a passionate world traveler and erstwhile antique dealer with a finely tuned sense of the quality of material objects. He trafficked in the sorts of exquisite, bespoke artifacts that are only made for the very rich, sniffing-out and acquiring them in part because he understood and loved both the things themselves, but also the high society which they had been made to flatter. He also collected them because they were to a him a form of currency, his literal stock in trade. So, while a steady stream of wonderful things (including not a few cherished family heirlooms) found their way into his hands, he just as quickly sold or bartered them off — much to the chagrin of his relatives — to keep the furnaces of his restless lifestyle burning. As my father often gruffly said of his big brother, there was no thing in his life that was “not negotiable for cold hard cash.”

I, too, have become a collector of fine things, but mine are generally more flawed and relatably human: artworks that are very good but probably not great; ancient pieces of furniture that have been worn down through many generations of use by people much like myself and which are usually more practical than decorative. My New England forebears, who are famous for their colonial furniture, nevertheless practiced a vernacular sort of artisanry engineered more for realistic use than for luxury, their most elegant decorative flourishes usually being relegated to those parts of the furniture that one would actually see on a day-to-day basis and the hidden parts being fairly plain and even sometimes crude. Even when some of these objects that have fallen into my hands are of a more “blue chip” quality, they at least tend to have collected some devaluing cracks and dings along the way. It is unlikely that anyone will ever make a fortune at auction selling the artifacts I have amassed. And yet, they are all exceptional in their special ways, mainly due to the deep histories they encode which are personally meaningful to me.

The two things I care most about are people and objects, in that order, and the latter only to the degree that they have become the physical repositories of the former in those persons now gone who collected, made, used and loved them before they came into my hands. Some of these are people I knew and loved myself, others go farther back through lines of descent that can be traced from my own present through relatives, friends, colleagues, employers or other makers of whom I was aware and admired, but never personally got to know. As such, the things I accumulate and keep are never gathered by me for commercial gain or re-sale; they are not investments. I collect them because I feel both a passion and a responsibility to care-for and steward them for whomever might end up caring for them when I in turn have gone. A carpenter friend once told me that a maker’s mortality is capped at the end-date of his or her last surviving creation. So long as I preserve these things, as well as their stories, then that maker remains in some sense alive, and all the better when it is a maker I personally knew, or to whom I have some other intimate or meaningful tribal or cultural connection.

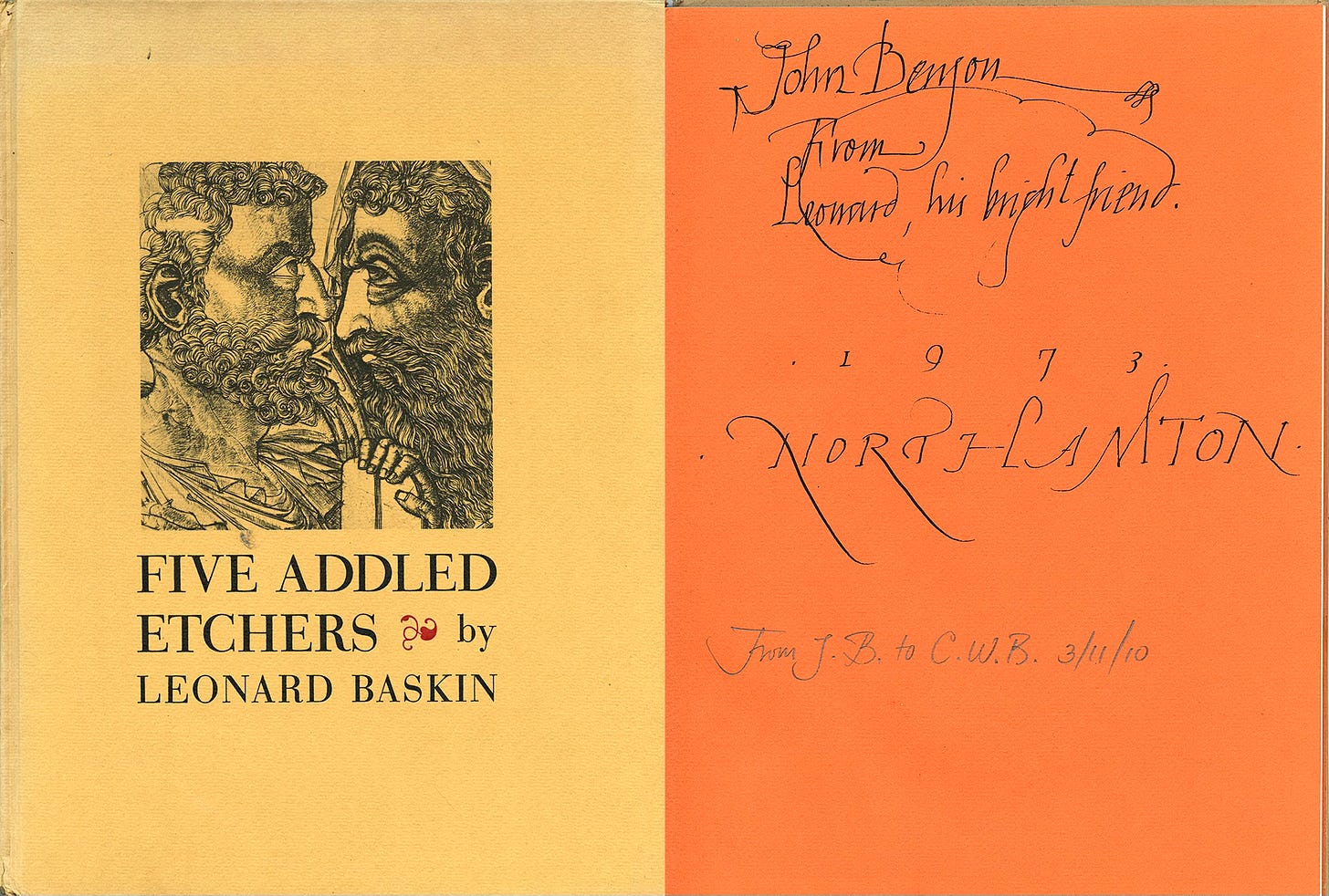

One such treasured object is a well-worn copy of a book written and published by the American wood engraver, etcher, sculptor and typographer Leonard Baskin, an important friend and mentor to my calligrapher father. Its title, Five Addled Etchers, tells the reader straight-off that it surveys a small group of possibly wayward, certainly unconventional, artists whom Leonard personally liked well enough to immortalize in his own idiosyncratic Canon.

I only met Leonard Baskin once when I was very young (seven or eight years old) when we went as a family to spend a few days at his idyllic artist’s compound on Little Deer Isle in Maine. I wasn’t old enough then to engage or be engaged in any sort of meaningful conversations with the guy, but I watched and listened carefully throughout that stay and the whole experience went on to have a defining influence on my later life, both as a painter, but also as a person who has consistently built his own worlds and economies, often in defiance of the conventions that others — both outside, but also within the world of art — might have otherwise imposed. The ‘Addled Etchers book thus has myriad layers of meaning to me. It calls that remembered visit to mind, while also demonstrating, in the works of its featured artists, the kind of creative magic that such unconventional oddballs are capable of brewing. It is also an example of one artist standing apart from the realm of academic critique, and speaking straight from the shoulder of his own practical knowledge in praise of an art form whose subtlest nuances he is probably far better positioned to understand. Finally, the book is also a talisman of the influential, often humorous friendship that these two larger-than-life artistic characters built. In all these different aspects, this one book has acquired a vitality all its own. Much more than a mere object, it is a vessel containing not only the memory of the people through whom it came to me, but in the very much alive personalities of the artists who are its subject; in that of the artist who saw and gathered them together as a group; in the relationship between that man and my own father, and finally in the influence that all these different people and their ways of being have exerted on my my own personality, work and lifestyle.

3. Jonas

Newport, Rhode Island is famous for two things. One was its long tenure as the site of the America’s Cup yacht races. It is even more well known, however, for the long avenue and “Ocean Drive” at the southern tip of the island where the oligarchic Robber Baron industrialists of the Gilded Age built some of their most ostentatious “cottage” mansions. The grandest of these houses, such as Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Breakers, Mrs. Astor’s Beechwood, and The Elms have been kept intact by a preservation organization ever since their monied owners quit the town, or their descendants saw those originally massive fortunes dwindle away. They are now visited annually by hordes of tourists, some offloaded from enormous cruise ships parked in the harbor which ironically dwarf the comparatively tiny summer houses.

When these palaces were being built, many of their components (often whole rooms at a time) were imported to the States from similarly palatial houses in Europe. Even so, there were always parts which had to be built new on site, or else reproduced in facsimile to fill the gaps that a new design or the vagaries of trans-Atlantic freight had occasioned. Because so few native craftspeople were up the standards demanded by the ornate decorations of those interiors, European artisans were often imported right alongside the filigreed components of mantles, grand stairways and coffered ceilings destined for installation in Newport. Italian stone carvers and masons were in particularly high demand, as were English builders of casework and furniture, and German woodcarvers, all of whom plied refined trades dating back to the Renaissance and even to the Gothic arts of the middle ages.

In the 1920s, my grandfather, John Howard Benson, purchased and assumed the management of a little colonial-era stone carving shop at the top of the town’s main commercial street. Newport was then home to one of the largest Naval bases on the east coast and he was hired early-on to carve a headstone for one of the Admirals who served there. Either the Admiral himself, or else one of his family members, desired that the eagle, shield and oak leaf decorations of a flag officer’s cap should be carved at its top.

Howard (as he was called) had a relatively stylized approach in his relief carving at the time and less experience with the sort of naturalistic representation that this device demanded, so he went up to “The Avenue” in search of a more classically-trained mentor to help him get it right. There he found an elderly German woodcarver — presumably an in-house artisan at one of the big cottages — named Jonas Bergner. Bergner carved a beautiful eagle in wood that became the prototype for the final version in stone. In the course of this collaboration, the two men became friends and remained so for the rest of the older one’s life. When Bergner died, he left a handful of carving chisels, a big tool-chest and his massive workbench to my grandfather.

4. His Bench

Traditionally, at least in the European trades, a woodworker’s bench is the first thing he is allowed to make on his own, and only then after serving for a time in more menial tasks like “picking up the shit and putting it in the shit pile.” During a brief tenure as an apprentice furniture-maker in my Swiss boss’s shop in Brooklyn, I was also required to build my own bench before being permitted to put my hands on any more refined projects. I didn’t do a stellar job. The bench worked well enough, but my technique was clumsy. Such things are often the catalogues of a novice’s inadequacies, the proverbial “first pancake” that is sometimes rightly thrown away. So, while it is clear from his beautiful Admiral’s eagle that the elder Bergner became an exceptional carver, and was probably an equally able shaper of moldings and builder of casework, his workbench is, to put it kindly, something of a beast, and therefore a likely early effort. Its construction, though heavy in weight and grandiose in aesthetic pretentions (with classical columnar supports at the corners supporting its massive maple top), is rather sketchily patched together, its many large and small tool drawers loosely dovetailed and their rough-sawn poplar sides and bottoms often assembled off square or milled in mismatched widths and thicknesses. If Bergner was in his seventies or even eighties when he left the bench behind early in the last century, it would be fair to assume that it was made by him as a young man shortly after the Civil War, which would make it at least a hundred and fifty years old today.

The workbench was relocated from Bergner’s to my grandfather’s shop sometime in the 1920s or ‘30s, where it stayed parked at one side of the big back carver’s room for the next fifty-odd years. I grew up climbing on it, working with my dad on various projects fixed in the jaws of its gigantic vises, and rooting — when unobserved — through the cavernous interior of its drawers, home to all manner of esoteric tools and other cast-off artisanal bits and bobs. During the shop’s renovation in the early 1980s, it was finally removed to a cold, damp cinderblock “barn” behind the shop to make way for a new iron woodstove. There it stayed, gathering dust and mildew for another decade, then off to an even colder commercial storage unit beside the Navy Base when my father tore down the cinderblock barn and built a new studio there for his sculpture.

I finally rescued the bench from storage in 2001 when my wife and I were building a new house and shop in eastern RI after moving back from a long sojourn in New Mexico and California. Our second son, Fisher, was born there that year. Over the next six years, I used the bench for various woodworking, car and motorcycle projects, then left it with a woodworker buddy in Vermont when we moved west again to Santa Fe in 2006. It was just too big for the truck to New Mexico and our rental there had no room to accommodate it.

This past July, the freshly college-graduated Fisher and I took a trip in my cargo van to the east coast to visit family in RI and New York and to retrieve a big etching press that I had recently purchased from a printmaker friend in Western Massachusetts. I got Skip Kelly, my woodworker pal to come down from Vermont and help load the heavy press in a U-Haul trailer, and he suggested before we set out that this might be a good time — the both of us getting a mite long in the tooth — to finally bring Bergner’s bench home to yet another Benson family shop, that it might eventually be handed down again to one of my own artisan sons.

We converged at the printmaker’s shop in MA and loaded the bench in pieces into the van and trailer alongside the printing press. The next day, Fish and I set out to haul the whole load back to Santa Fe, where it arrived at my shop almost nineteen years to the day from when we had left it behind.

Needless to say, given its long and checkered history of moves and storages, the bench was somewhat the worse for wear on arrival, many of its always less than perfect joints and fitments having long since begun to fail. Almost all the drawers and their old wooden glides needed rebuilding. The base cabinet itself was cracked and broken in many spots as was the massive top. Beside all of that, decades of neglectful, damp New England storage had played hell with the finish, such as it was, and left a gray, six-inch skirt of bleached, moldy and water-damaged bare wood at the floor like the mud at the hem of Elizabeth Bennett’s dress when she first visits Mr. Darcy. Hauling it into my garage shop, I was a little bit dismayed at its rough condition.

But once I got into it, the restoration quickly became a project of simply cleaning off the years of grime, reconditioning the dried-out places where water and other environmental insults had done their damage, re-fastening and re-glueing the reparable bits, then rebuilding and replacing the parts that were too damaged to fix. Wood is such a forgiving and malleable material, probably because it was once alive. Bringing back its luster — which is not so hard to do, given the right materials — is so much a process of re-enlivening it.

Gradually, I got the base cabinet cleaned up and oiled. I glued together the biggest structural cracks in the top, re-built the slides for the big vise on the left end, and belt-sanded then applied multiple coats of oil and wax to the top until it shone again, albeit showing all that scrimshaw-like residue of cuts and scores across its surface that had come from so many years of hard use.

The hardest job has been (and continues to be) the rebuilding of the drawers, which were so badly worn, with their glides dug out into bow-shaped depressions and with the sides coming apart and the bottoms falling out. This is still an ongoing project, but the largest drawer, shown here below, is an example of a total rebuild, utilizing the original poplar sides, but cutting them clean along their length, front to back, gluing new straight poplar edges to the bottom, then recreating a central, slotted support that had completely fallen apart.

There are still many jobs to do, such as fashioning some stout hardwood jaws, probably in black walnut, for both vises, neither of which closes all the way. I also plan to line all the smaller drawers with some new natural-finished birch plywood and attach dividers to create tailored slots for specific tools. It’s all a lot of work that will go on for some time. But now, at least, the major structural elements are whole and functional, and they also look pretty nice!

The truth — which I don’t always admit to myself, much less to anybody else — is that I didn’t much like being a woodworker early in my life. I resented that I needed to do it to support my painting, which I’d have preferred to do to the exclusion of all else. But by the time I was in my thirties, I was making a solid living as a painter and the woodwork gradually receded into the background, to be called on only in occasional market slumps or when I was building furniture and cabinets or renovating houses for my own family.

In the past decade or so, I have actually started to enjoy woodworking. Like the people who made the kinds of things I like to collect, I am a good craftsman, not a masterful genius. I make practical things solidly, carefully and well; things that I hope will continue to be used and cared for long after I’ve gone. Little by little over the past weeks, I have brought Jonas Bergner’s workbench — and in a sense, also Jonas himself — back to life. It is not a pretty thing, but it has a kind of rough and honest beauty and integrity. And I, as a now older artisan, have a chance to incorporate it into the working furniture and equipment of a little renaissance in my own craft; to find in myself the bits of Jonas that the bench and its history have bequeathed first to the other makers in my family, and now to me.

Grazie mille for bringing "back to life" not only Jonas Bergner and his bench, but countless characters and places mentioned in this captivating account. The major structural elements in the bench are beyond "pretty nice" and seem instead like art itself. And imagining some of the stories that the bench might tell, I'm wondering do you and/or have you ridden moto(s)? With thanks once more for another lyrical and lovely ride......

Charming! Reminded me of my all-too-brief apprenticeship with Seth Persson, Saybrook boat builder. You knew my godfather, Lloyd Hyde, right? Somewhere, I have his written tales of flying around back country India during the depression, buying chandeliers. He disassembled them, shipped the glass fragments home, and reassembled them in NYC. Made a lot of dough. His bankers thought he was utterly daft!

A well spent life, young man! May you keep on keeping on!