The painter Michael Allen recently wrote in his fine Substack column Damned Hard Work about a watercolor by Andrew Wyeth. His piece sent me down a rabbit-hole of memory and, if not exactly of regret, at least spurred some winsome re-examination that feels long overdue, especially in light of the kind of paintings that I have always most liked to make.

I, like Michael and so many other American painters who came up in the decades when Wyeth was at his productive peak, was taught early-on to look down on him as an exemplar of all that modern art commanded us to revile. When I first encountered him as a teenager in the early 1970s (when Abstraction and Pop topped the heap of the postwar movements in contemporary art) Wyeth was seen as too reactionarily wedded to the provincial conventions of pre-modern Northeastern realism and the discredited ethos of the American Scene. But of all his supposed crimes against the reigning orthodoxy, Wyeth’s most unpardonable sin may have been that of a certain illustrative sentimentalism that his critics tied to the Greenbergian aesthetic transgression of “Kitsch.”

However satisfying this assessment may have felt to those who needed to put Wyeth in that box, it never felt fair to the far more varied and masterful achievements he attained. Never mind that a great many of his actual narratives, far from romanticizing their subjects, convey a dark undertone of psychic unease and uncertainty that doesn’t comfortably fit into any ready cultural container; his pictures were also impeccably executed across a range of languages that traverse from the raw, painterly gesture of his nearly-abstracted watercolors, to a level of naturalistic refinement in his most polished tempera portraits, landscapes and architectural compositions that Bronzino or Van Eyck could have admired. That mastery was one of the crucial points of Wyeth’s artworld exile, I imagine because he was able to do things that a great many of his contemporaries who basked in the critical limelight at that time could not do. How much easier to ask “why would we want to” than to admit that you simply can’t?

Please understand that this is not the opening salvo in a polemic against Modernism. I am very much a Modernist myself — both in the formal realism that I have practiced throughout my working life, and in the abstractions I have painted alongside that representational work over the past twenty-five years. I love Modern art when it is masterfully made. But it is only fair to point out that some of it is not, and that the anti-traditional ideological proscriptions that encouraged a generation of artists and critics to cast Wyeth out, simultaneously enabled plenty of mediocre, and even frankly inept, practitioners to win acclaim on purely ideological or fashionable merits.

That said, neither is this a tirade in favor of methodology. There are as many highly accomplished, even dazzlingly facile classically trained painters whose work is fundamentally vapid, as there are aesthetic ideologues who have mastered no skill whatsoever. As the Scottish painter and architect Charles Rennie MacIntosh once so succinctly put it:

There is hope in honest error; none in the icy perfections of the mere stylist.

No — mastery means a great deal more than merely doing things skillfully or in a certain way, and that truth applies equally at either end of the Traditionalist / Modernist or Modernist / Postmodernist divides that so polarized artists, especially here in the US, in my lifetime. As much as Wyeth is skilled, so is he human and flawed. His observations are in no way pat, however much we can instantly recognize his visual language as his own. For me at least, his flaws are also integral to his mastery.

I grew up with a collotype print of a figurative Andrew Wyeth picture hanging in the stairwell in my grandmother’s house which clearly demonstrated this fact of his human complexity. It is one of his coarser, more stilted efforts, so not an overly facile or refined example of his skills. But it’s a strong picture nonetheless and was, to my boy self, at once a deeply familiar but also deeply strange, even uncomfortable image, offering no immediately clear summation of narrative intent.

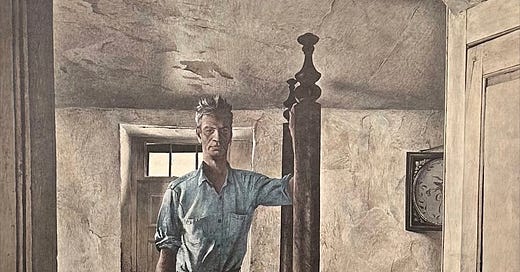

In it, a tall, rangy man dressed in a blue chambray work shirt and baggy brown trousers stands off-center in a spare room with peeling plaster walls, one hand resting at the top of a Colonial four-post bed. Apart from the corner of a pale, white, chenille bedspread, and one half of what looks like a framed floral needlepoint on the far wall, the room contains no other adornments apart from the warped rails and stiles of a raised-panel closet door with a hand-carved wooden catch barely holding its straining frame inside its jamb.

It is only now, a quarter century on from the selling of that house and the disappearance of that print from my daily life — that it occurs to me that everything portrayed within it was also materially present in the house and world that in turn contained both it and me. It hung at the top of a landing which, if I crossed it to the left, opened into a nearly identical room of peeling plaster, also holding a Colonial four-post bed, opposite which, along one wall, an identically warped raised-panel closet door was restrained with an identically hand-carved pivoting catch.

The similarities between these worlds did not end with the physical surroundings portrayed, but also included both the man and all that his sartorial identity and hand-hewn container telegraphed about the culture that had produced him. Were I to wander through my grandmother’s ramschackle New England house in 1967 or ‘68, when I was first becoming conscious of this picture’s presence, the men I’d have encountered there (my father and his two brothers) — coming and going through its kitchen and into its cellar of musty tools and marine hardware, or its backyard with busted bits of cars, motorcycles, boats and harvested architectural details from other falling-down colonial houses — very much resembled the man in the picture. They too wore the uniform of the threadbare chambray work-shirt, a surplus inheritance from the enlisted men who served in the Navy in those postwar decades and which so many artisans and workers adopted in those days. All of them knew how to make things like those seen in the painting, as I too later learned the trade of building raised paneled pine cabinet and closet doors and hardwood bedsteads. The observation I would have offered to Wyeth’s detractors back then, had I only known how, would have been to say that, YES, the picture portrays the world that also contained it, but not sentimentally. It instead telegraphs the hardness and self-sufficient practicality of that northeastern Yankee culture in a way that is not merely admiring or romantic, but also admits that it can be an oppressive, closed-in world and one not allowing for much in the way of a divergence from either its received economic and spiritual paradigms, nor their embedded aesthetics.

Throughout my childhood and early teens in the late 1960s and early 70s I had no idea that Wyeth had even made this picture, though I was an early admirer of his father’s robust oil-painted illustrations in the Scribner’s Classics children’s books that could also be found on the library shelves in that same house. I only knew that it was a portrait of a family friend from my grandmother’s childhood summers in the 1920s at Chadds Ford in the Brandywine Valley of Pennsylvania. The man in the portrait, named Arthur Cleveland, was affectionately called “Cousin Punch” by my grandmother and her siblings, though he was in fact no blood relation of theirs. But he was related in other ways, being so plainly a citizen of the America that they all inhabited in that time, and in whose craggy, John Brown-like visage can be seen the ghosts of similar Yankee men who had fought in our wars, built our houses, farmed our fields, worked in our mills, and sailed our ships going all the way back to the first Europeans to land in the Americas. Again, there is nothing to me sentimental in the characterization I see there. It is truthful and plain, and a bit agnostic as to any specific benevolence or malevolence residing in that history.

So then, why was Wyeth’s vision deemed so wrong, so backward or so deserving of our collective aesthetic or ideological contempt? I honestly do not know. I do know that I’ve spent my life disagreeing with and rejecting the mindset that needed to see him, or anybody else (myself included) in that way.

I admire Andy Wyeth’s abilities and achievements. As is true with every other painter or other sort of artist whose work I admire, I don’t like everything he made. There are surely some pictures where he strained a little harder than he perhaps needed to in order to elicit a particular response in his viewers. But then we all do that sometimes. The key is to paint through that impulse to lecture or illustrate, and to find the place where the far more complex truth of the world — and of what we sometimes discover in the process of rendering it — can be seen as it actually is.

Much as I have at times been instructed to do so, I just can’t conclude that doing that job with exceptional skill and artistry should ever be seen as any kind of a failure.

I remember thinking his work was slick. But I really appreciated his deft handling of water color when I saw his work in Maine more recently. And I respect the hours he will have spent learning his trade.

I will posit as a philistine troglodyte that Andrew W came from the lineage of illustrator and that the moderns could not abide that.

Howard Pyle, Maxfield Parrish, and Andrew's pater, N.C., were very-very skilled artists, but oooh so Commercial; (Max selling jello; dats icky.)

although i suspect they might have been irked that they were not seen as 'Fine' they got where their bread was buttered. By a time the world of illustration had gone to pasture and the skills had been denigrated but Andrew made his nut with the skills of his heritage.