I got fired last week by one of the galleries where I show my paintings. This happens from time to time. I’ve been showing in art galleries since my late teens, about forty-six years now. This is the second time I’ve been fired by one, and both instances were in the heavily commercial, gallery-saturated market of Santa Fe, New Mexico. It is only fair to admit, however, that in both these cases, I actually brought the firing on myself by drawing lines in the sand of our respective partnerships that I knew neither dealer would accept. I did this in the first instance by changing my style radically away from what that gallery had been successfully selling; in the second, it was by making paintings that the dealer and I both thought might sell well, but insisting on a level of free-agency for myself that made them uncomfortable.

I have nothing against the folks who let me go. They are good people and have their ways of doing things. I have my ways of doing things too. Sometimes these ways diverge. I’m not here to talk about them. I wish them well.

The more interesting question to me — and one that I have been asking myself since I first began showing in commercial galleries here in Santa Fe in my late twenties — is what does the artist/gallery relationship mean? Why does it exist, and what can it accomplish? What does the gallery get out of it, and what do they want? What does the artist get out of it and what do they expect? Artists of every sort, and at every age, grapple with these questions. Many of us spend years pining after representation, believing, as we’ve been taught to do, that the gallerist is the fairy godmother or father who will wave a wand and bestow all that we crave: an income, respectability, fame, perhaps even immortality.

Maybe.

But why do we want all those things in the first place? The need for an income is easy enough to understand; I get that one. We all want to be able to pay the bills so we can continue to make our art instead of slinging hash, or sheetrock, or pushing paper or a computer keyboard for somebody else.

But fame, respect, immortality? Famous to whom; everybody on earth? Do we mainly want to be famous to all those people who have enough money to buy our art?

And who’s respect are we looking for? Do we want the respect of all people everywhere, of the culture in which we live, or only of the handful of folks who actually know what it is that we’re trying to do, i.e., the ones who “get it”?

As to immortality, nobody can give us that. It either happens or it doesn’t that our work is remembered after we go. Some artists achieve great fame in their lifetimes only to fade or be eclipsed as public tastes and cultural conventions shift. Others live lives of obscurity only to be “discovered” decades, or even centuries after they’ve died. Still others labor all their lives, possibly even making great work, which is simply thrown away, lost or destroyed when they die because they never made their work sufficiently well-known while alive to create an audience that would want to have it. Upon their death, a family member is suddenly saddled with a studio, a barn or a storage unit crammed with works they have no idea what to do with.

Then what?

For whatever reason, as a very young person just picking up a paintbrush for the first time, the idea that got into my head was that the whole point of being a painter was to do it as well as humanly possible. I wanted to learn how to make extraordinary things. That’s all. My “art” therefore resides in that pursuit, and in the effort to communicate meaningfully human experiences within the pictures I paint, as well as to make things that you want to go back to and look at again and again, and when you do, to find something new each time.

Is this what galleries want from their artists? Sometimes it is, or at least it is one component of what they want all of the time. But what they also want is a product to sell, something dependably recognizable with an identifiable and memorable “brand”, and ideally with new examples being turned out just infrequently enough to keep the collectors a tiny bit hungry for the next release, but often enough so that the gallery doesn’t have to wait too long for a fresh supply. It’s a little bit like drug dealing.

So then, another important question is this: is this the way art should even be made in the first place, as a sort of product line engineered for the market? And if not, what kind of work does this business model, which now dominates the whole behemoth, globe-straddling contemporary art market, actually foster, encourage, and create?

I don’t need to tell you the answer to that one. Just walk through the galleries and art fairs in New York, Miami, Basel, Venice, or wherever else this commercial bazaar has shot its many tendrils. It’s a giant department store filled to overflowing like a cornucopia of art-like products. There is of course a lot of good art nestled in amongst other things that are a bit more superficial, a bit more pat, a bit more predictable. But the challenge is always to see it as such when our senses are so overwhelmed with so much competing material which, while equally eye-grabbing, provocative or colorful, just isn’t quite as good.

It may sound as if I am setting myself up here as a rare diamond in this sea of paste. It is true that we artists all think we are wonderful and tragically under-appreciated. A teacher I had in art school — a very funny man named Richard Merkin — once said to our class “Who (other than yourself) is the greatest living painter?” We all laughed because he was partly right. Still, I don’t love everything I make, and I don’t actually believe that I’m the greatest at anything . . . yet. But therein lies the truth of it. It isn’t that I think I am a great painter, but that I am always aspiring to become one. And the problem I’ve had with the commercial galleries right from the start, and more-so with myself in relation to them, is that when I am making art for the market, art that I am confident will sell, it isn’t always my best art. It may be very appealing, because I am skilled enough and have enough of an eye to know what people like to buy and hang over their couches. But it isn’t always reaching past that plateau of desirability to something more challenging or deeper, not only for the viewer, but also for myself.

I am not suggesting that all those things I’ve made for the market over the years are bad things. They are every bit as good at being what they are as the similarly marketable works made by earlier artists who also had to find a life-supporting trade. We see this in Rembrandt’s portraits of wealthy merchants, in Turner’s elaborate watercolor depictions of grand English country houses, and in Goya’s portraits of the Kings and Queens of Spain. But none of those workaday, market-tailored idioms are quite what we revere those artists for, are they? No, it’s Turner’s near-abstract maelstroms in pictures like The Slave Ship or in Rain Steam and Speed that we remember him for.

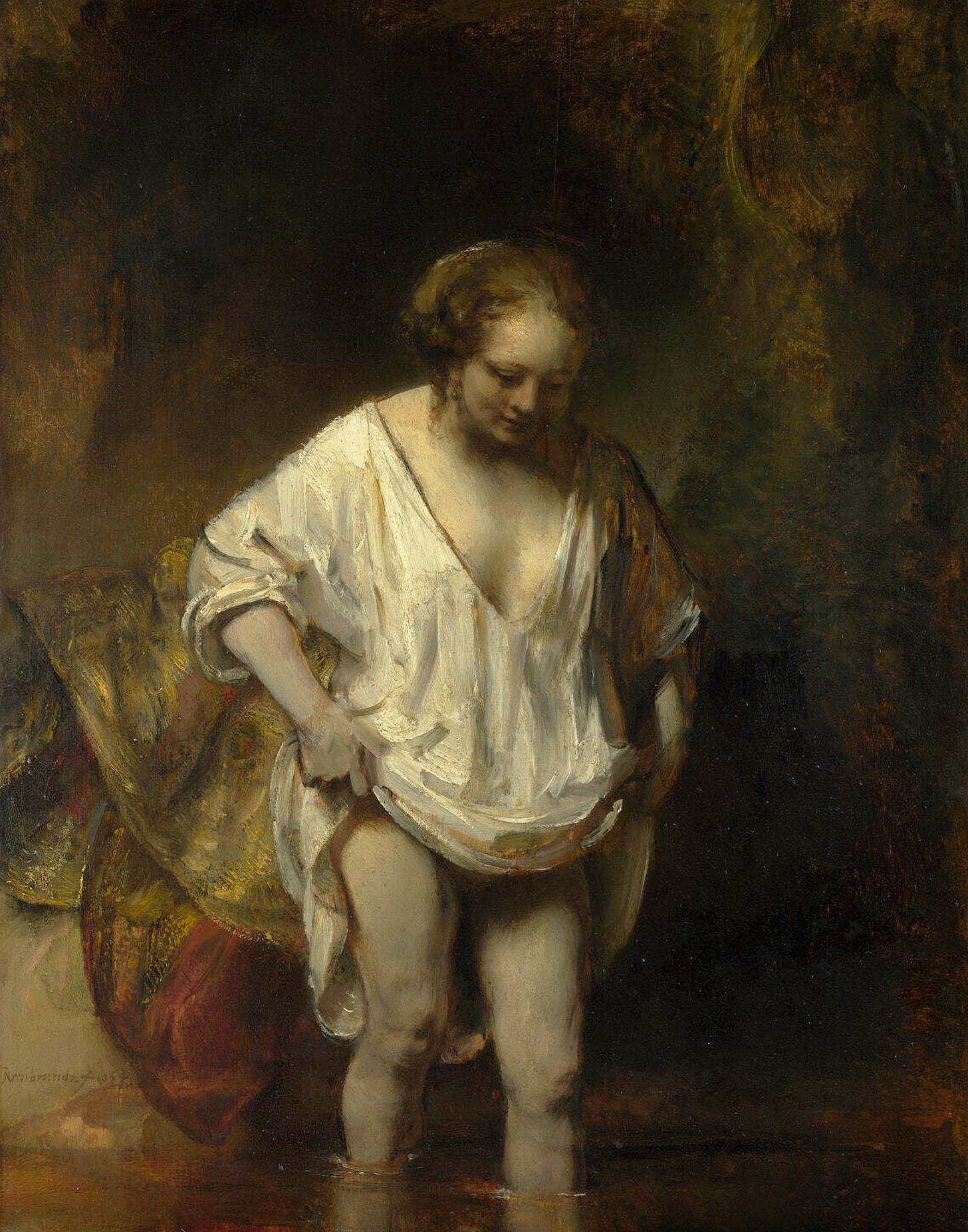

It’s Rembrandt’s incandescent rendering of A Woman Bathing in a Stream, or his etched biblical scenes and landscapes that can actually transport us.

It’s Goya’s Black Paintings and his etched Disasters of War and Los Capriccios that we put up on a higher pedestal than his jobbing court portraits.

I’ve been fortunate over a now very long career to make most of my living as a painter. I do other things to earn money too, but painting was always the main event that took precedence over everything else. I was included in my first museum exhibition in the late 1970s at age nineteen and have been showing and selling work in commercial galleries all over the United States ever since. I have also sold a lot of work on my own, gradually building networks of patrons, collectors, friends, and family members who have all liked my pictures well enough to buy them and hang them on their walls. As I said to a pair of artworld friends over drinks the day I was let-go by the gallery, of the six hundred or so oil paintings I’ve made in my life, I only personally own about thirty of them. I’ve destroyed a few and have overpainted others. I’ve given some away to friends and family. But the rest are all out in the world. They’re either hanging in people’s houses, or else have been put in storage. A handful are even in museums. Some have surely been lost, or otherwise neglected and damaged by their owners. I know of at least five that are irrevocably faded from having been hung in full sunlight for years on end. I can only guess at the condition of all those ones whose whereabouts are now unknown to me.

My paintings are quite good, but they’re not quite great, at least not by my standards. I’ve gotten close once or twice, but the market always comes back in and exerts its pull to make that nice thing for over the couch, that pretty piece of decoration that will pay the mortgage, cover a college tuition bill for one of our boys, or take care of a credit card that got out of hand because I racked up a big balance on art supplies and framing. It is not my dealers’ fault when I get fired by a gallery. It is my fault for making an unhappy Faustian bargain in the first place. Somewhere back before all this began, I met a devil at the crossroads who gave me some talent, but who quietly inserted the poisoned pill that what it suited me for best was to make pretty things that people would buy, but which would never rise any higher so long as that was why I was making them. The trouble I have — the reason I always eventually leave, or else get terminated by the commercial galleries — is that I want something more, and I know that as long as I’m making what the market wants, I won’t get to it. In a way, I have been desperate to get fired by this system for the past thirty years

The other side of this coin is the fear and uncertainty that maybe this is all that I have to offer; that all I will ever be is a facile painter of pretty things; that any efforts to rise higher will cause me, like Icarus, to spiral down, splash and disappear into the sea. But as maudlin as that may sound, it is the reality that anyone who aspires to transcend the ordinary must inevitably face. And at nearly sixty-five, it is surely worth a shot. I have been longing for years to walk away from this engine of commerce that always seems to get between me and the art I really want to make. I have no idea whether or not I’ll succeed, but why not give it a try?

As to fame? I corresponded for about ten years with a very famous (and also very good) oil painter. He was kind and generous and deeply knowledgeable about our shared vocation. At one point I received a little postcard from him that simply said “you are one hell of a painter.” To me that’s worth ten thousand minutes of the kind of fame that Andy Warhol predicted we’d all get to have, and it isn’t fame at all. It is, rather, the acknowledgement and recognition of someone who knows the difference between the ordinary and extraordinary.

The rest is for the paintings themselves to determine. If they really are extraordinary, they will still be here long after I have gone. If they aren’t, oh well — I got to spend my life making them, and that’s pretty hard to beat.

My eyeballs can’t wait. Go wild.

Good thoughts on this conundrum. I was in a prominent Santa Fe gallery in the 2000s, and I was fired in the aftermath of the 2008 crash. Perhaps galleries are again tightening their rosters as the market becomes more uncertain.

While I was with that gallery, they had me raise my prices substantially and do costly framing (even on stretched canvases which I didn't think needed it). After I was fired, my prices were too high for other markets. We are told to never lower our prices because collectors will be upset. It took me years to gradually lower my prices.

Another aspect of all this is the pressure to produce, leading artists to sell work that is slapdash or too-quickly-released before the artist can hone the work to a higher level. This happened to me and the quality of my work decreased.

Currently I have minimal involvement with just one gallery, and I'm enjoying the freedom to explore. Yet, how do I get my work out into the world instead of accumulating in storage, only for my nephew to deal with when I pass? (If I don't get the work out there, why should I expect him to do so after I'm gone?) Also, the IRS wants to see a profit motive if an artist wants their endeavor to be considered a business, not a hobby.