A printer and book artist friend called me recently following a conversation with a colleague about the apparently complete absence of descriptions, in books on Craft, about the Book itself as the product of a highly evolved craft and art.

These two gentlemen were the eminent San Francisco Bay Area letterpress printer, book artist and book fair impresario Peter Koch, and the New York based typographer, letterpress printer and book artist Russell Maret. Both men are featured in an illustrated collection of essays about art and craft that I published with my brother (the letter carver and lettering artist Nick Benson) in 2022, titled ART IN THE MAKING, Essays by artists about what they do.

A very young Russell Maret, assisting Peter Koch on press in Venice, 2006.

Peter had remarked to Russell on the failure of all the craft-related volumes in his own extensive library to make any mention at all of the making of books; whereupon Russell responded that ours might be the only volume of that kind that actually does so. I had no idea when I was compiling the essays for that project that there was anything unusual about choosing to include book artists in the collection, but now that this discrepancy has been brought to my attention, it seems fitting here to write something about how the form came to be, and to point out both its long history as an exceptionally refined craft, as well as what a lively, diverse and internationally engaged artistic discipline it has lately become.

I first visited Berkeley, California in the Spring of 1988, where I crashed at the apartment of Christopher Stinehour, a chum from a renowned New England family of book printers, and a former letter-cutting apprentice of my father’s. I also met and fell in love there with my future wife, who is the stepdaughter of the late Bay Area printmaker and poster artist David Lance Goines. Cybele and I were later married in Berkeley and lived there together throughout the 1990s, where I was soon immersed in that city’s community of artists and craftspeople. But my first experience of living in the crafty Bay Area was in the summer of 1989, when I briefly shared an Oakland studio with my friend Chris, and his shop-mate, Mr. Koch.

Koch, Stinehour and Monique Comaccio in the “Real Lead Saloon” at CODEX in Berkeley.

Long a hothouse of artisanal and artistic practice and experimentation, San Francisco, Berkeley and Oakland, alongside the other cities ringing that bay, began as early as the turn of the last century to produce indigenous artforms as diverse as the Craftsman architecture of Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan, the Modernist painting movement of the Bay Area Figurative school, the Farm-to-Table cuisines of Alice Waters’ Chez Panisse and Deborah Madison’s Greens restaurants, the Acme Bread company, and myriad other small, single-owner, artisanal ateliers, kitchens and studios. But one of the most concentrated and experimental artisanal movements to come out of that region over the past half century has been its unusually high concentration of lettering arts, letterpress printers, hand binders and book artists. This tradition began in the 1920s with the Grabhorn Press and has carried on through to the present in the works of Adrian Wilson, Jack Stauffacher, Ward Dunham, Peter Koch, Thomas Ingmire, Andrew Hoyem, William Everson, Julie Chen, Richard Siebert, the bookbinders Eleanore Ramsey and John DeMerritt, and the typefounders Mackenzie and Harris. There are of course other fine letterpress printers all up and down the Pacific coast as well, such as Carolee Campbell’s Ninja Press in Los Angeles, the Foolscap Press in Santa Cruz, and the Triangular Press in Portland, Oregon, to name just a few.

We tend to associate San Francisco with the Beat Poets, the Westernized Zen Buddhist movement and the 1960s countercultural Rock and Roll Bacchanals of the “Summer of Love.” But there was a far earlier countercultural movement from which Hippiedom generally, and many of the arts of left coast derived some of their spirit. The English Art and Crafts movement in the nineteenth century kicked off the modern notion of a humanistic rebellion against the perceived spiritual sterility and material mediocrity of industrialization – a revolt reborn yet again in the Hipster “Maker” culture of today, which similarly pushes back against the over-engineered “economies of scale” of the dystopian rise of Big Tech and AI. It is a tad ironic then that the letterpress-printed book, which is one of the more complex and nuanced hand-assisted crafts still in use today was, in its origins, the prototypical innovation of industrialized mass production. Prior to the arrival of Herr Gutenberg’s bibles in the fifteenth century, a book was an object made entirely by hand, and in one unique copy. Similar additional copies of, say, an illuminated manuscript, a scripted ledger or a ship captain’s rutter, might have been made one after the other, but each would nevertheless remain a fully unique product of a single maker’s art, its text and illustrations having all been hand-scripted, drawn or painted one page at a time. All of that changed with Gutenberg’s inventions of moveable type and his printing press, which together enabled the production of single sheets in the thousands, and books — like that renowned Bible, which was printed in 180 copies. It may be for this reason that books thus mechanically produced are neglected in studies of the single-maker, single-object craft ethos, or that the form is excluded from consideration as an art. But an art they are nonetheless, and a quite sophisticated art at that.

Art is, of course, a much contested term. In the five centuries after the Italian Renaissance, it was confined — here in the West at least — to relatively high-minded aesthetic or religious (and often also political) objects such as paintings and sculpture, where the term of Craft was reserved for more practical workaday things like furniture, clothing, crockery, textiles and commercially illustrative printed matter. But in the hundred years between the late nineteenth and late twentieth centuries, both Modern and Postmodern artists — concurrent with the introduction of mechanical, chemical and later digital photographic processes into the canon of artistic methodologies — changed all of that. Over the past fifty years, Art has come to incorporate almost anything thoughtfully made (and even some things simply found or acted out) which incorporate any higher than strictly commercial expression of philosophical inquiry or cultural critique. This broader definition was the guiding principle for our essay collection, in which we strived to include as wide an array as possible of contemporary artistic disciplines, some of which would have been more sharply segregated away from art in the past. Among them, we included the making of artistic books, whose latter evolutionary phase has more or less unfolded since the end of the Second World War, with Leonard Baskin’s Gehenna Press and Harry Duncan’s Cummington Press leading the way, trailed over the following decades by Claire Van Vliet’s Janus Press, Walter Hamady’s Perishable Press, and Andrew Hoyem’s Arion Press. Earlier instances of course also exist, such as in the work of the visionary Regency period English painter and printmaker William Blake, not to mention in the Liber Studiorum edition of printed re-interpretations of J.M.W. Turner’s paintings from that same era.

This is perhaps an essay for another day, but there is an artisanal sweet spot which occurs at the confluence of a new mechanical innovation’s most perfectly distilled potential and the persisting governance over its operation by the human eye and hand. Just think how aesthetically beautiful and physically pleasing the products of earlier industrial eras can be, and how collectible, as artifacts, they have now become — the Corliss Steam Engine, the Brough Superior Motorcycle, the Bailey pattern Smoothing Plane, John Browning’s 1911 Colt .45 automatic pistol, or a race-car engineered by W.O. Bentley, Harry Armenius Miller or Ettore Bugatti. Despite all being quite functional, such things incorporate so much residue of direct handmade design and manufacture that they are now seen as works of a kind of art and are often even included in the collections of our top museums.

Similarly, the mechanical making of books has, throughout its evolution, incorporated so many intimately integrated functions of human design and handmade craft that man and machine have melded within the discipline into a conjoined and cooperative locus of deliberate artistry.

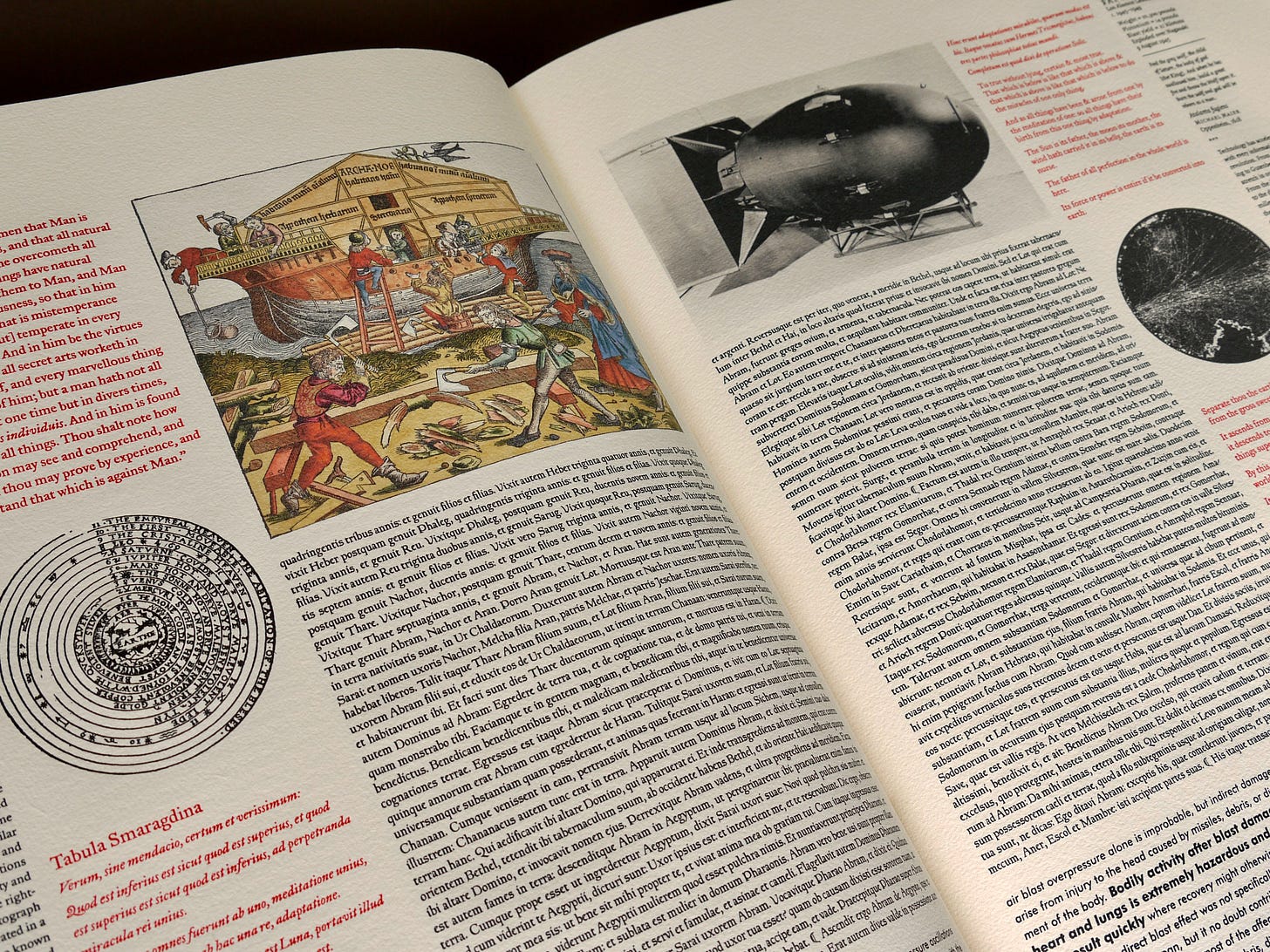

Between the time of those first mass-produced bibles in the mid-1400s and the invention of the first rotary offset lithographic printing press in 1875 (and the industrialized Smyth bookbinding processes that evolved at roughly the same time) the making of books was a craft that married a wide range of hand-made components to Gutenberg’s comparatively efficient industrialized methods of manufacture. Letterpress printing is exactly what its name describes — a relief-cast or carved letter, numeral or symbol, fashioned in metal or wood, onto which a film of ink is applied, and which is then pressed into a sheet of paper. This results in a physical impression on the sheet which has both material depth and a strong graphic impact.

As elegant as this method is for rendering bodies of text in print, the illustrations that often accompany such texts are similarly physical handmade things, having first been hand-drawn, then later hand-engraved into, or relieved from, wood or metal blocks and plates. Such blocks are then assembled with the type forms in a metal frame called a chase and locked in place with separating blank filler blocks called furniture, and strips of lead or steel acting as typographic spacers, in order to make the impression forms for each page.

Type set and locked with furniture into a chase, prior to inking and printing.

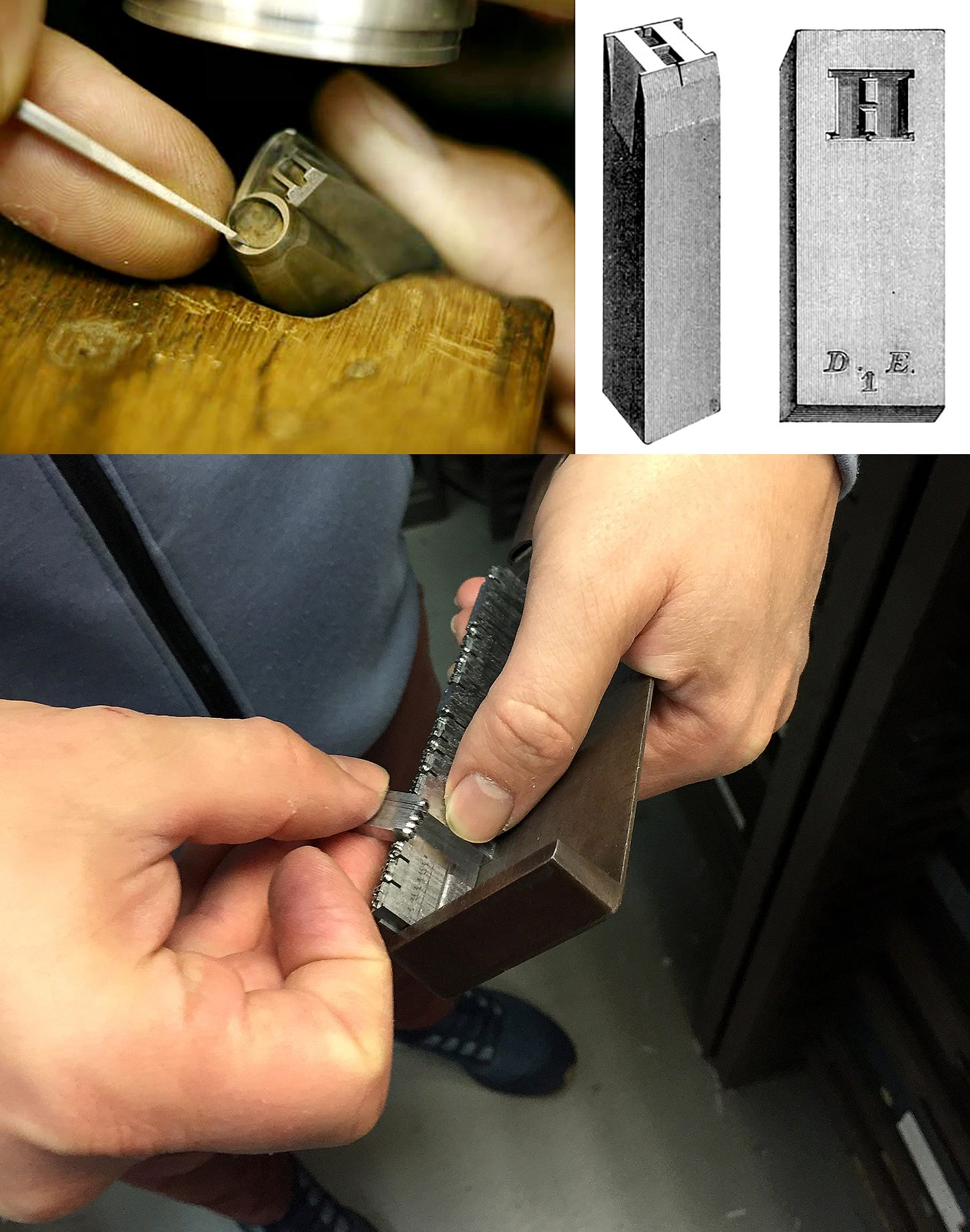

All of the manufacture and coordination of these components is done by hand and with acutely careful design by eye. But at an even more elementary level, the finest pieces in the play — the letters themselves — also marry human and machine in an elegant apotheosis of the best potentials of both. The alphabetic letters, numerals and figures of movable type are each initially drawn by somebody’s hand. That drawn or inked prototype is then used as the pattern for the, also hand-executed, relief carving in soft steel of a metal punch, which is hardened and then hammered into a copper or brass matrix. The matrix becomes the basis of a mold that is fashioned around it, and into which the molten lead for each piece of type is then poured and cast.

Top: A punch being cut and an illustration of punch and matrix. Bottom: Lead type being set by hand in a composing stick.

The finer European books made by these methods between the fifteenth and early twentieth centuries also tended to be printed on durable, handmade cotton and linen-based “rag” papers. Wood blocks and laid rice papers were the more common materials in Asia which also has a strong letterpress-style printing tradition which pre-dates Gutenberg’s invention by centuries. The sheets, thus printed, are then assembled in multiple hand-sewn signatures which are then glued into bindings that are hand-bound in wooden or cardboard covers laminated with fine cloth or leather and often stamped with figures and typography in gilded or colored metal foils.

Some book making artisans master several of these disciplines for the creation of their own works. More commonly though, the whole art of book manufacture — by these means at least — comprises a collaborative orchestration of many differently skilled performers, so that even today, when contemporary book artists might take on as many of the parts as is practical, they also often spend a good deal of energy in sourcing materials made by other makers, some who are living and others having long since passed — from the type-designer, to the punch-cutter or engraver, to the typefounder, the maker of inks, the paper makers and the binders. Each represents a uniquely skilled performer in the orchestrated whole that a finished book represents. At the end, many differently capable sets and eyes and hands have played a part in this kind of book’s creation. Ultimately though, it is the typographic designer, who may also be the actual printer, or any one of the other skilled artisan participants, who imagines and then assembles all the parts into a whole work. He or she is the symphonic composer of the work, whose own skillset must incorporate a deep knowledge of the qualities and histories, the limitations and potentials of each of its contributive components. Besides all that there are the additional skills of understanding how the texts must alternately stand apart and flow together, how any included illustrations should best be sequenced throughout the narrative so as to contribute as seamlessly as possible to its message and meaning.

Two letterpress pages from Peter Koch’s “Speculum Mundi.”

Like so many other early confluences of hand craft and industry, the letterpress-printed book — in the full bloom of its most evolved practice at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries — was a practical craft which also secretly incorporated extraordinary art. But when new technologies rendered its commercial viability mostly obsolete, it was then positioned to be reclaimed, reconstituted and redefined by a new generation of loving practitioners as an art in itself. Determining exactly where and how a craft transforms into an art in this way is always an interesting, and sometimes hotly debated topic. But it is actually simple enough, so long as we take a broader than purely philosophical or cultural view of what art’s purpose actually is. There is an historical path, along which our human understandings, skills and technologies evolve. As tempting as it may be to think of that path as a straight road of progressive advance from earlier and inferior, to later and necessarily superior practices, it is far more like a serpentine flow of water through a winding channel that periodically eddies, slows, makes turns that reverse its course, or occasionally becomes dammed to the point of bursting to flow once again in a torrent. Every age makes its own self-interested determinations about the most desirable nature and definition of Art. But throughout all those shifting cultural fashions and tastes, the inherent qualities of the most thoughtfully and skillfully made human artifacts quietly persist. This process is occurring now in the community of book artists who still view craft as central to the realization of their art. Every other year, hundreds of such artists flock to the Bay Area from around the world to display and discuss their wares at the CODEX Biennial International Book Fair & Symposium which was founded by Mr. Koch and his wife Susan Filter, a paper conservator and world traveler. Thousands of enthusiasts travel similarly long distances for the opportunity to see and touch these remarkable books.

The champions of the zero-sum games of science and tech like to cast their works in Darwinian terms of the survival and ascendancy of the fittest or smartest of our human achievements. If they were right about that, our whole delicate life-supporting global ecosystem would not now be teetering at the brink of total collapse. At their best, both Craft, and also Art, open a window into another capacity we possess, which is our ability to develop and refine the most elegantly sophisticated cooperative ballets of the old Greek terms of Ars and Techne — of humankind’s ability to, not only invent, but also to govern and use the tools of its most useful technologies in ways that transcend the demands of mere material efficiency or commercial gain to reach a plateau of elevated accomplishment. This, at the end of the day, is where art actually happens. And the craft of making books is one of its most fascinating and rewarding expressions.

At the biennial CODEX Book Fair in Richmond, California in 2019. Left to right: my late father, John Everett Benson, myself, and next to us, my son William, Alani Rathweg and Barbara Tetenbaum. J.E.B. and I were there to present a book about the letterer John Howard Benson (my grandfather) on which he and I had collaborated that year. Will and Alani came along with Barb, an exhibiting book artist and their department head and advisor in the Book Arts program at the Oregon College of Art and Craft – C.W.B.

Congratulations on highlighting the Art of the Book. My late friend Paul Getty II built a beautiful library at his English Country Estate dedicated to it. I have collected fine books since childhood and will always regret having shied away from buying one the finest books ever made,published at Venice in 1499 by Aldus,The Hypnerotaumachia Polifili in a splendid binding because of its dauntingly high cost. Need I tell you that 20 years later that book is worth fifteen times what was then asked…